This glossary provides brief definitions and requirements for easy reference by FisheryProgress.org users. For more details, please refer to:

- Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions (CASS) Guidelines for Supporting Fishery Improvement Projects

- FisheryProgress FIP Review Guidelines

- FisheryProgress Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy, version 1.1

A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

An action is a major activity from the FIP’s social or environmental workplan that must be completed to address the deficiencies identified in the needs assessment (for basic FIPs), MSC pre-assessment (for comprehensive FIPs), risk assessment (for social performance).

Examples of environmental actions:

- Peru mahi-mahi - longline (WWF): Action: 1.2.1 Development and Implementation of conservation measures

- Vietnam yellowfin tuna - longline/handline: Action: 2.1.1. Document the catch of species in the handline and longline fisheries

- Japan albacore tuna - longline: Action: Assess gear impacts on habitat

Active FIPs are currently at Stage 2, 3, 4, or 5 and are implementing their environmental workplans,, and reporting progress to FisheryProgress.org. (Source: CASS Guidelines for Supporting Fishery Improvement Projects, 2021). Active FIPs can be either basic or comprehensive (defined below under FIP types). Active FIPs on FisheryProgress.org are also satisfying requirements outlined in the FisheryProgress Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy.

Basic FIPs are a good entry point for fisheries to begin addressing specific environmental challenges to improve their performance against the Marine Stewardship Council Fisheries Standard. Basic FIPs complete a needs assessment to understand the challenges in the fishery.

Taking, in good faith, all reasonable steps with the goal and assumption of reaching the desired end. It includes doing everything known to be customary, necessary, and proper for ensuring the success of the endeavor.

At minimum, proof of budget must include a list of main expenses and revenue sources for the FIP. A more comprehensive budget could list all of the costs associated with each activity, as well as secured funding and needed funding for each activity. A budget may anonymize or aggregate the sources of revenue, and may include in-kind contributions as well as monetary contributions. A FIP must update the budget once per year.

Completed FIPs have provided independent verification that they have completed all of their [environmental] objectives. (Source: CASS Guidelines for Supporting Fishery Improvement Projects, 2021) For many Completed FIPs, this means they have graduated to MSC full assessment. Completed FIPs on FisheryProgress.org no longer report on their environmental performance but may choose to voluntarily report on their social performance.

Comprehensive FIPs aim to address all of the fishery’s environmental challenges necessary to achieve a level of performance consistent with an unconditional pass of the Marine Stewardship Council Fisheries Standard. Comprehensive FIPs engage a party experienced with applying the MSC standard to complete an MSC pre-assessment to understand the challenges in the fishery and must have independent, in-person audits of progress against the MSC standard every three years.

This requirement is currently under revision. We ask that FIPs refrain from completing this requirement until it is launched in early 2022.

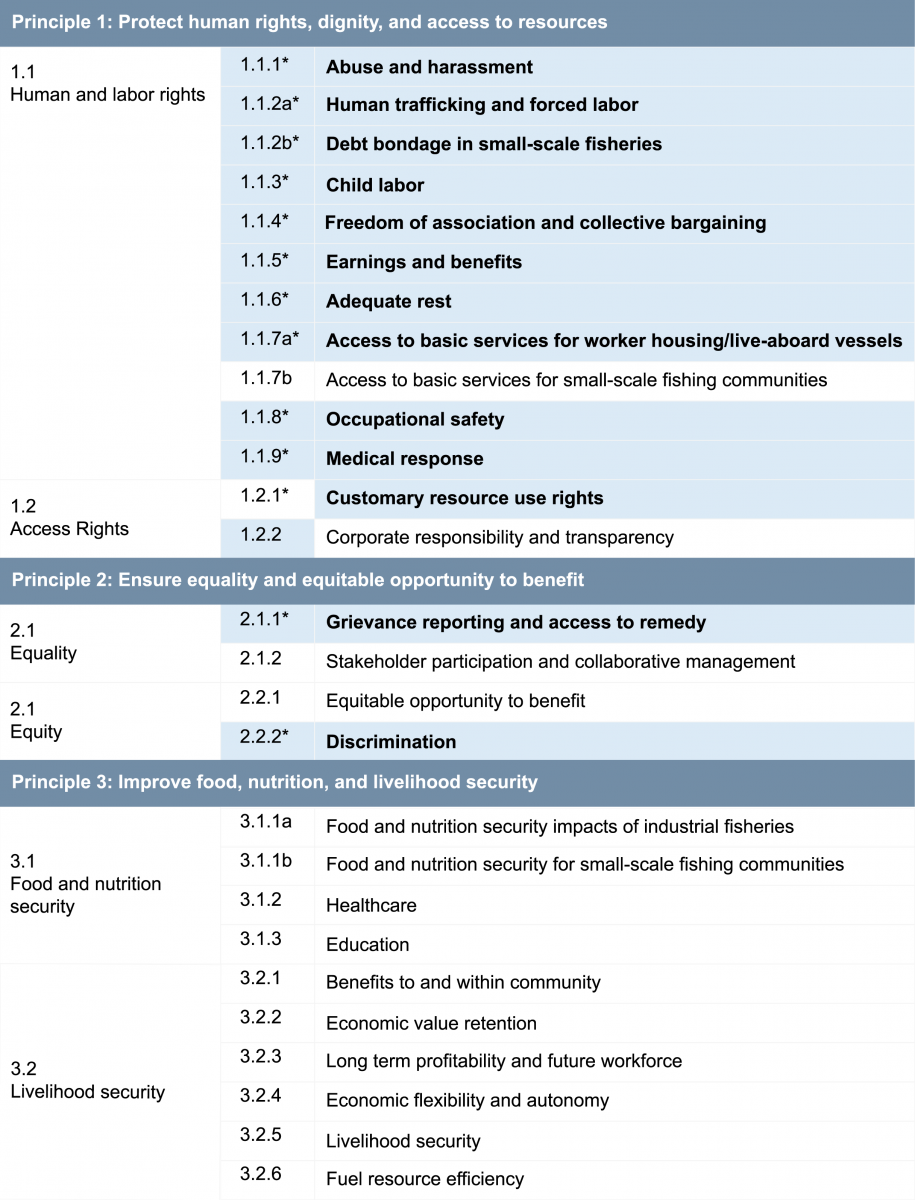

- Core FisheryProgress SRA Indicators

The table below presents the full set of SRA performance indicators (PIs). The PIs highlighted in blue and noted with an asterisk (*) are the Core FisheryProgress SRA Indicators. These are indicators that:

- Are required to be assessed (as applicable) for FIPs that meet one or more of the criteria for increased risk of forced labor and human trafficking (see Requirement 1.5 and 2.1).

- Must be assessed by an individual or team with the qualifications outlined in Appendix C of the FisheryProgress Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy, regardless of whether the FIP is required to assess them or is doing so voluntarily (see Requirement 2.1 and 3.1).

The estimated weight of the product a FIP catches at the time of landing, in metric tons. The estimated landings of the FIP is a subset of the Estimated Total Fishery Landings; however, only the landings from FIP participants or landings sold to FIP participants in the FIP’s Unit of Assessment should be considered.

The estimated weight of the product a fishery catches at the time of landing, regardless of the state in which it is landed (e.g., whole, or gutted or filleted). The estimated landings of the fishery should match with the scope of the FIP’s Unit of Assessment, which is defined as 1) the target stock(s); 2) the fishing method or gear; and 3) the fleets, vessels, individual fishing operators, and other eligible fishers pursuing that stock.

A workplan includes a list of actions the FIP will undertake to meet its environmental objectives, a breakdown of specific tasks under each action, organizations or people responsible for completing each action, and a month and year deadline for completing each action. Each action must be linked to the MSC indicators it means to address. Review the following examples of an environmental workplan:

- Bahamas spiny lobster – trap/casita

- Federated States of Micronesia yellowfin and bigeye tuna – longline

- Honduras Caribbean spiny lobster – trap

- Tokyo Bay sea perch – purse seine

FIPs must provide evidence of progress on actions in the workplan and, if needed, additional evidence for changes in indicator scores.

Evidence will vary depending on the actions. The following are examples of different kinds of evidence for action progress:

- Signed agreements with consultants, government, or others demonstrating progress on specific activities such as research.

- Meeting agendas, notes, and/or participant lists.

- Letters sent to governments, suppliers, or others.

- Media articles, blog posts, and/or statements posted on a website.

- White papers, summary reports, rapid assessments, formal stock assessments, or data analyses.

- Data collection protocols, log books and catch documentation, or raw data.

- Official government laws, regulations, or policies.

Score changes may be driven by action progress (see above) or by demonstrated improvements in policy, management, or fishing practices or improvements on the water. Evidence will vary depending on the improvement reported. The following are examples of different kinds of evidence for various environmental improvements a FIP may report:

- Policy change

- management plan, ministerial decree, or media coverage documenting policy change.

- Change in fishery status

- government or third-party reports showing improvement in fishery (e.g., stock assessment). Changes in fishing practice government or consultant report, or summary report from FIP coordinator. For fishing practice changes, evidence must clearly state what proportion of the fishery has implemented the changes.

- Research

- peer-reviewed study, consultant or government report, or grant report that confirms data being collected.

Countries have jurisdiction over the exploration and exploitation of marine resources within 200 nautical miles of their shores.

- Existing FIPs

All active FIPs, including both basic and comprehensive FIP types, reporting on FisheryProgress before the relevant Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy requirement effective date. This also includes FIPs that have already submitted a profile to be listed as active prior to the relevant policy requirement effective date.

The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has defined 27 major fishing areas around the world.

Individual in charge of making changes to the FIP profile on the website. It’s the primary contact for FP and the FIP Reviewer to answer questions and submit reports.

The individual or organization designated as the main point of contact for the FIP for FisheryProgress. Users may contact the FIP lead with questions about the FIP or to learn more about engaging with and/or sourcing from the FIP.

Objectives define the near-term scope of the FIP and must be specific, measurable, and time-bound. Basic FIP objectives address a specific set of the environmental challenges identified in the needs assessment to improve the fishery’s performance against the MSC standard. Comprehensive FIP objectives address all of the fishery’s environmental challenges necessary to achieve a level of sustainability consistent with an unconditional pass of the MSC standard. Examples:

- For a comprehensive – FIP Achieve MSC certification by 2020.

- For a basic – FIP Promote the use of gear that diminishes environmental impacts by 2017. Promote full compliance with fishery regulations by 2018. Implement traceability programs to increase the producers’ transparency and accountability by 2020.

Any entity that actively participates in a FIP by contributing financial or in-kind support to the project and/or working on activities in the workplan. FIPs are required to have active participation by companies in the supply chain. Other important participants include government, fishery managers, and nongovernmental organizations. (Source: CASS Guidelines for Supporting Fishery Improvement Projects, 2021)

Seafood product(s) harvested from the FIP’s target fishery and sold either directly or indirectly to FIP supply chain participants. FIP product includes all seafood product(s) caught and sold within the Unit of the FIP– i.e. products landed from vessels/fishers recorded on the vessel/fisher list and sold to supply chain actors identified as FIP lead(s) and/or FIP participants.

FisheryProgress staff member who reviews FIP profiles and serves as the main point of contact for FIPs within FisheryProgress.

FisheryProgress.org recognizes six FIP stages of fishery improvement project progress, defined below, along with four status definitions. While the path to improvement is not always linear, these stages and status descriptions help groups and companies evaluate improvement projects and make decisions about engagement and/or sourcing. Source: CASS Guidelines for Supporting Fishery Improvement Projects, 2021).

- Stage 0: FIP Identification

Target fishery identified and supply chain analysis conducted. - Stage 1: FIP Development

Assessment of the fishery’s environmental performance conducted and participants recruited. - Stage 2: FIP Launch

Participants and workplan finalized and made public. Budget adopted (but need not be public). - Stage 3: FIP Implementation

Workplan implemented and progress tracked. - Stage 4: Improvements in Fishing Practices or Fishery Management

Demonstrated improvements in policy, management, or fishing practices documented. - Stage 5: Improvements on the Water

Demonstrated improvements on the water documented.

FIP status helps identify where the FIP is in its process and whether it is actively reporting on FisheryProgress.org. FIP statues include Prospective, Active, Inactive, and Completed. FisheryProgress only tracks progress on active FIPs.

- FIP Supply Chain Participants

FIP participants that buy or sell FIP products. This includes both companies and their representatives (e.g. distributors, exporters, foodservice providers, importers, processors, producers, retailers, vertically integrated companies, and trade organizations).

FisheryProgress tracks two types of active FIPs – basic and comprehensive. The primary differences between basic and comprehensive fishery improvement projects are the level of scoping to inform development of the workplan, the objectives, and the verification required. Both basic and comprehensive FIPs must conform to the requirements outlined in the FisheryProgress Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy.

Any person of any age or gender employed or engaged in the capture or gathering of seafood, either from shore or from a fishing vessel. Fishers also include persons employed or engaged in any capacity or carrying out an occupation on board any fishing vessel, including persons working on board who are paid on the basis of a share of the catch but excluding pilots, naval personnel, other persons in the permanent service of a government, shore-based persons carrying out work aboard a fishing vessel and fisheries observers.

A description and evidence of the FIP’s efforts to make fishers aware of their rights under the Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy, including the FIP’s commitment to improvement under its Policy Statement and the availability of grievance mechanisms and how to use them. See Requirement 1.3 of the Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy for additional information.

An independent specialist authorized by fishery regulatory authorities to collect data to assist in the monitoring of commercial exploitation of marine resources (e.g., species caught and discarded, area fished, gear used). At-sea observers join the vessel during fishing trips but do not normally engage in fishing activities; they observe fishing practices as a third party, and report scientific and regulatory enforcement information to the management authority.

Any voyage during which fishing takes place. The duration of a fishing trip includes all time spent away from the port(s) of origin. That includes but is not limited to time spent at-sea, docked in foreign ports, soak time, and time spent resting in remote areas without access to communications.

A formal, legal, or non-legal complaint process that can be used by fishers that are being negatively affected by certain business activities and operations.

An ongoing risk management process followed by a company in order to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how the company addresses its adverse human rights impacts. It includes four key steps: assessing actual and potential human rights impacts; integrating and acting on the findings; tracking responses; and communicating about how impacts are addressed. (Adapted from the https://www.ungpreporting.org)

Inactive FIPs are those that suspended work before achieving their objectives, have missed reporting deadlines, or have not reported results in three years. (Source: CASS Guidelines for Supporting Fishery Improvement Projects, 2021). See the FIP Review Guidelines and Social Review Guidelines for additional information on when FIPs on FisheryProgress are moved to inactive.

An independent audit is an in-person review of a FIP’s action results and performance against the MSC standard (e.g., changes in fisheries policy, management, or fishing practices and ultimately the health of the fishery) by someone who has demonstrated experience applying the MSC standard and is independent from the organization implementing the FIP. Independent audit reports are required for comprehensive FIPs every three years, and encouraged for basic FIPs.

When a FIP reports that it is complete and provides independent verification for the final claim it’s making about the environmental performance level it has achieved, the reviewer will move it to the Completed section of the website. Examples of claims and appropriate verification include:

- Claim: Certified; Independent Verification: Certification report

- Claim: In MSC full assessment; Independent Verification: Publicly announced and not on exited list, with at least one of the FIP participants listed as a client group

- Claim: Meets a level of performance equivalent to an unconditional pass of the MSC Standard (i.e., a comprehensive FIP that does not pursue certification): Independent, in-person audit that affirms all indicators are green (and meets FisheryProgress’ audit guidelines) posted publicly on FisheryProgress

- Claim: Rated; Independent Verification: Assessment report

- Claim: Met specific objective such as bycatch reduction; Independent Verification: Independent evidence–government report, peer-reviewed paper, etc.

A FIP must upload materials to verify its initial baseline environmental indicator scores. If a FIP’s pre-assessment or needs assessment includes baseline scoring and supporting evidence, the assessment can meet this requirement. If not, the FIP must submit additional documentation to support its baseline scores against the environmental indicators.

A permanent number assigned to ships for identification purposes. (Source: IMO).

Vessels that weigh 10 gross tons or more, or measure 12 meters or longer.

FisheryProgress.org uses 28 indicators based on the MSC Fisheries Standard version 2.0 as a common measuring stick for all FIPs on the website. The MSC Fisheries Standard is accessible to all fisheries regardless of whether they decide to pursue certification. The standard was developed in consultation with scientists, the fishing industry, and conservation groups. It reflects the most up-to-date understanding of internationally accepted fisheries science and best practice management. The 28 indicators fall within three core principles: 1) sustainable fish stocks; 2) minimizing environmental impact; and 3) effective management. If you’re unfamiliar with the MSC standard, this guidance document may be helpful.

A Memorandum of Understanding is one way of demonstrating the participants in a FIP. It should clearly identify the FIP scope or name, names and organizations of participants, specific terms of agreement (e.g., funding/in-kind support and/or activities to be conducted by each participant), and end date, and include confirmation that all parties have signed the MOU. FIPs are encouraged to include their policy statement(s) in the MOU..

A needs assessment is an evaluation of a fishery that covers the three principle areas of the MSC standard to determine environmental challenges and improvements needed in the fishery. It may not assess the fishery’s performance against every MSC performance indicator at a detailed level.

- New FIPs

All FIPs, including both basic and comprehensive FIP types, that submit a profile to be listed as active on FisheryProgress after the relevant Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy requirement effective date.

A documented agreement a FIP and/or its participants employ to publicly disclose responsibilities, commitments, and/or expectations regarding, at a minimum, human rights and social responsibility. The policy statement may come in the form of a code of conduct, commitment, policy, guidelines, standards, or other document.

A pre-assessment is a preliminary evaluation of a fishery against all MSC performance indicators to provide a picture of the fishery’s baseline environmental performance and challenges. A pre-assessment allows a fishery to identify any areas that need to be improved to reach an unconditional pass of the MSC standard. A pre-assessment must be completed by someone experienced with applying the MSC standard (e.g., is a registered MSC technical consultant or accredited auditing body). Review the following examples of a pre-assessment:

- Argentina offshore red shrimp – bottom trawl

- Eastern Indonesia yellowfin tuna – handline

- Tokyo Bay sea perch – purse seine

FIP Progress Ratings, developed by the Sustainable Fisheries Partnership, use time benchmarks to quickly understand the rate at which a fishery is improving on its environmental indicators. Each progress rating is associated with an alphabetic rating:

(A) Advanced Progress

|

(B) Good Progress

|

(C) Some Recent Progress

|

(D) Some Past Progress

|

(E) Negligible Progress

|

FIPs report twice per year, during a six-month and annual report. The report due dates vary by FIP, based on when they were listed as an active FIP on the site, and are noted on each FIP’s overview page. Six-month reports are when FIPs report on action progress. Annual reports are when FIPs report on action progress and provide an update on all of the FIP’s indicator scores, along with relevant updated documents.

Prospective FIPs are currently at Stage 0 or Stage 1 and intend to meet the requirements for basic or comprehensive FIPs and complete Stage 2 within one year. (Source: CASS Guidelines for Supporting Fishery Improvement Projects, 2021). Prospective FIPs may not report on social progress on FisheryProgress.org while prospective, but will be required to report on their social performance in accordance with the FisheryProgress Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy and Social Review Guidelines in order to become active.

RFMOs are international bodies made up of countries interested in managing fish stocks in a particular region. These include coastal countries whose waters are home to part of an identified fish stock and distant water fishing countries whose fleets travel to areas where a fish stock is found. To identify what RFMO a FIP might be in, visit the FAO website by clicking here.

The process of providing remedy for a human rights abuse and the substantive outcomes that can counteract, or make good, the negative impact of the abuse. See Remedy. (Source: Based on Shift/Mazars LLP).

Actions taken to resolve and prevent future negative human rights consequences resulting from business activities and operations. Actions may take a range of forms such as apologies, restitution, rehabilitation, financial or non-financial compensation, and punitive sanctions (whether criminal or administrative, such as fines), as well as the prevention of harm through, for example, injunctions or guarantees of non-repetition.

In the context of the FisheryProgress Human Rights and Social Responsibility (HRSR) Policy, a detailed assessment intended to identify social, labor, and human rights risks and challenges within a FIP and the context in which the FIP operates. Under the HRSR Policy, FIPs may submit an on-site evaluation conducted by a qualified professional of the indicators in the Social Responsibility Assessment Tool (SRA) or submit evidence of an alternative social assessment such as audit results from a social standard or certification, an academic research study, or another social risk assessment. See Requirement 2.1 of the HRSR Policy.

A scoping document summarizes the results of the needs assessment or pre-assessment and recommends strategies for addressing the fishery’s environmental challenges to help fishery improvement project participants develop an environmental workplan. If these elements are included in the fishery’s pre-assessment or needs assessment, a separate scoping document is not necessary. Review the following examples of a scoping document:

- Bahamas spiny lobster – trap/casita

- Ecuador mahi-mahi – longline

- Honduras Caribbean spiny lobster – trap

- Tokyo Bay sea perch – purse seine

A desktop evaluation of a set of situational factors that increase the risk of forced labor and human trafficking in a fishery. The self-evaluation is typically completed by the FIP lead. FIPs that meet one or more of the criteria must complete Component 2 of the Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy, including a risk assessment which will reveal the true degree of risk in the FIP. See Requirement 1.5 of the Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy for additional information.

The fisher having command of a fishing vessel.

Vessels which weigh less than 10 gross tons and are shorter than 12 meters.

A list of actions the FIP will undertake to address areas of risk identified by the FIP’s social risk assessment. For FIPs that have completed an SRA, the workplan must include the organizations or people responsible for completing each action and a month and year deadline for completing each action. It may also include a breakdown of specific tasks under each action. For FIPs that have submitted evidence of an alternative assessment, the workplan must relate to the findings of the alternative assessment. See Requirement 2.2 of the HRSR Policy.

Tasks break actions down into specific steps that describe how the action will be accomplished. Tasks provide more clarity on how the FIP intends to complete each action. Examples of environmental tasks:

- Peru mahi-mahi - longline (WWF)

- Action: 1.2.1 Development and Implementation of conservation measures. Tasks:

- Analysis of current measures in place for the conservation of the mahi-mahi stock (at national and international level) & identification of priority areas for implementation

- Design of research project on hook selectivity and other measures (as appropriate depending on existing information)

- Agreement on measures to be implemented as part of the overall harvest strategy for the conservation of mahi-mahi

- Establish a closed season for mahi-mahi in Peru

- Implementation of management measures (e.g. close seasons, hook size etc.)

- Action: 1.2.1 Development and Implementation of conservation measures. Tasks:

- Vietnam yellowfin tuna - longline/handline

- Action: 2.1.1. Document the catch of species in the handline and longline fisheries. Tasks:

- Establish an observer scheme to monitor all catches of retained species and document the level of discarding from the handline and longline fisheries

- Extend port sampling procedures to cover retained species (and informed by the observer scheme)

- Document observer data and port sampling verification, and prepare summary reports of main and vulnerable species (retained) interactions other than bigeye tuna.

- Action: 2.1.1. Document the catch of species in the handline and longline fisheries. Tasks:

- Japan albacore tuna - longline

- Action: Assess gear impacts on habitat. Tasks:

- Collect information on gear loss and actions taken to minimize the gear loss.

- Conduct research on fished habitats and about potential impacts on those habitats from lost longline gear

- If impacts are likely, develop and document measures to minimize the impact on habitat

- Implement a strategy to minimize habitat impacts and a monitoring plan to check whether the strategy is working.

- Publish report about the main habitats in fished areas and the fishery’s impact on these habitats.

- Action: Assess gear impacts on habitat. Tasks:

The unloading of goods and/or fishers from one ship and their loading into another to complete a journey to a further destination. Note that for Requirement 1.5 of the HRSR Policy, the risk criterion focuses on transshipment that occurs at-sea between large vessels only.

A fishery improvement project, or FIP, is a multi-stakeholder effort to improve the sustainability of a fishery. The Unit of the FIP (UoF) delineates the boundaries of the project, defined by the characteristics of the fishery and the supply chain actors that are involved in the improvement project. The UoF includes:

- The target stock(s),

- The fishing gear type(s),

- The defined subset of fishing and transshipment vessels or individual fishing operators pursuing that stock (listed in the FIP’s vessel list), and

- The supply chain actors identified as FIP lead(s) and participants.

A global unique number that is assigned to a vessel to ensure traceability through reliable, verified, and permanent identification of the vessel. (Source: FAO).

A vehicle used to catch or transport fish or fishers. That includes transshipment vessels. FisheryProgress defines vessels by their size, as outlined below. All vessels fishing or transporting catch within a FIP are included in the scope of the Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy regardless of whether they are formal participants in the FIP. See large vessels and small vessels.

The individual or legal entity that has assumed the responsibility for the operation of the vessel from the owner and who, on assuming such responsibility, has agreed to take over the duties and responsibilities imposed on owners. The vessel operator may be the vessel owner, the captain, skipper, manager, agent, or bareboat charter. (Based on the Maritime Labour Convention, 2006 definition for shipowner).

The vessel may be owned by one or several entities, including legal owners and/or beneficial owners that own or control the legal owner.

A workplan includes a list of actions the FIP will undertake to meet its environmental and/or social objectives, a breakdown of specific tasks under each action, organizations or people responsible for completing each action, and a month and year deadline for completing each action. See Environmental Workplan and Social Workplan for more details.